Memory Body

Project «Memory Body» was shown as part of the «Visually Invisible» exhibition at the Sandstone Gallery. The date of the exhibition: 16 May — 16 June 2024 was supervised by Sasha Kuznetsov

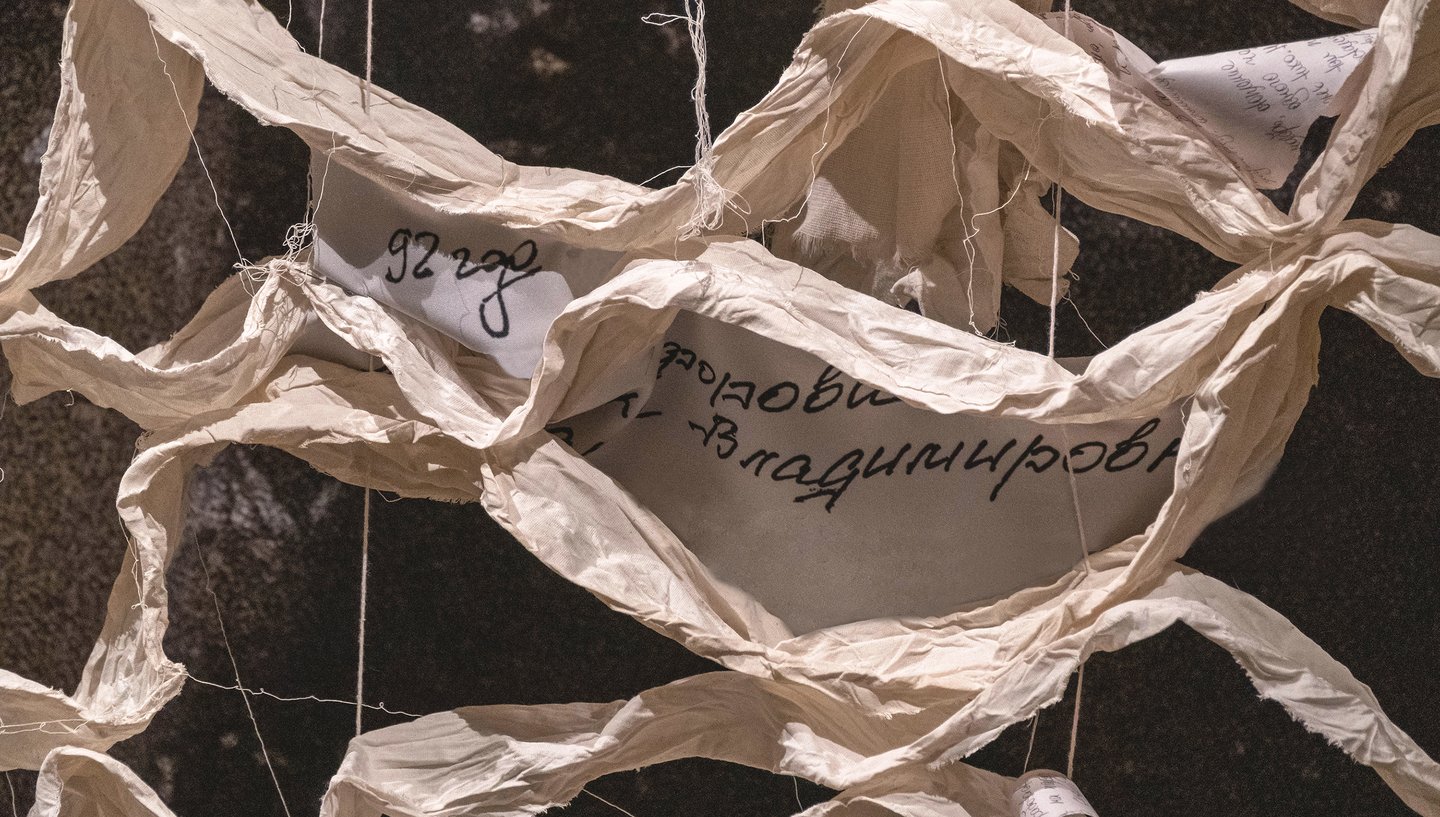

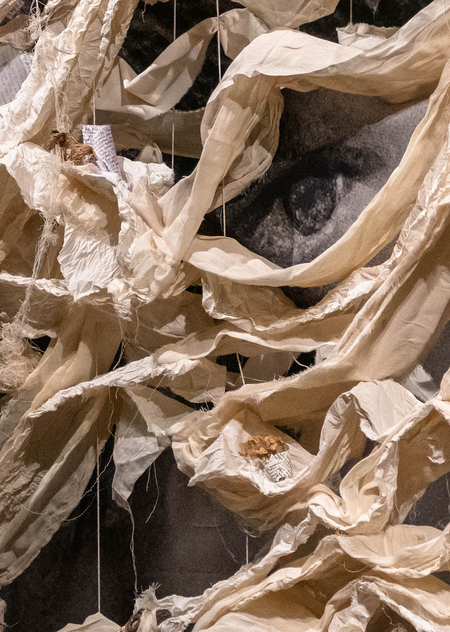

To talk about memory, I’m using the image of a living body formed by multiple interlocking of spatial threads. Memories are mobile, and when I imagine what matter they could be from, I see their relationship with biological forms — living, uncontrolled, and autonomous.

Memory is a private case of an archive that lacks a rigid regular structure. This archive is full of memories, material evidence of the past, voids, and lacunas.

The desire to preserve personal memory determines people — memory is what our communities hold on to, our sense of morality and ethics, and our understanding of ourselves. The preservation of memory, in many ways, makes us human.

The project is based on the stories of my personal memory, where loss and void are more important than facts and evidence.

The stories here are similar to their confusion and failure. They bind together into a single body, turn around in space, wrap around them with a bunch of sub-tests. These are stories from my experience, but at the same time, everyone can find familiar moments, roll-calls, feelings of belonging.

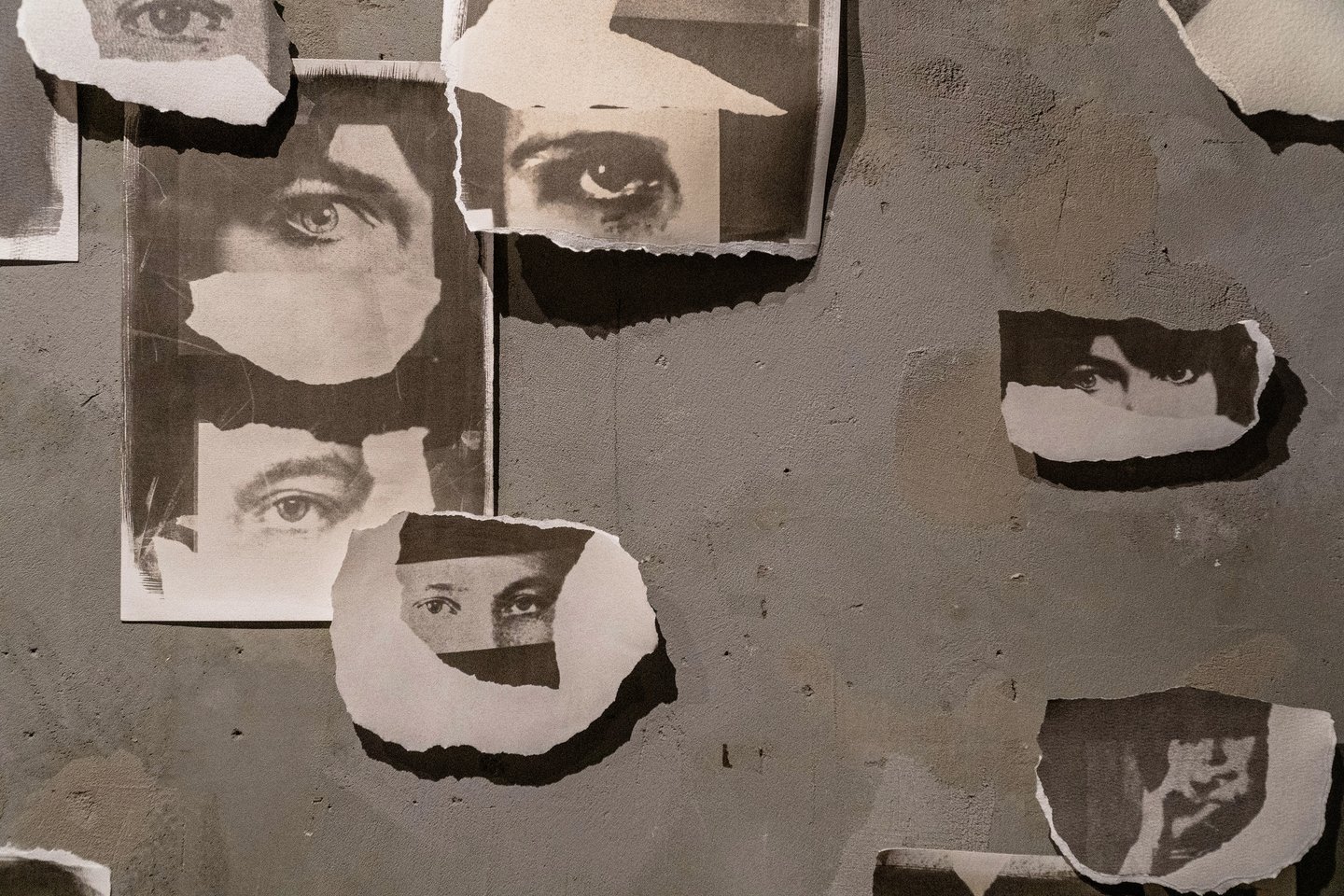

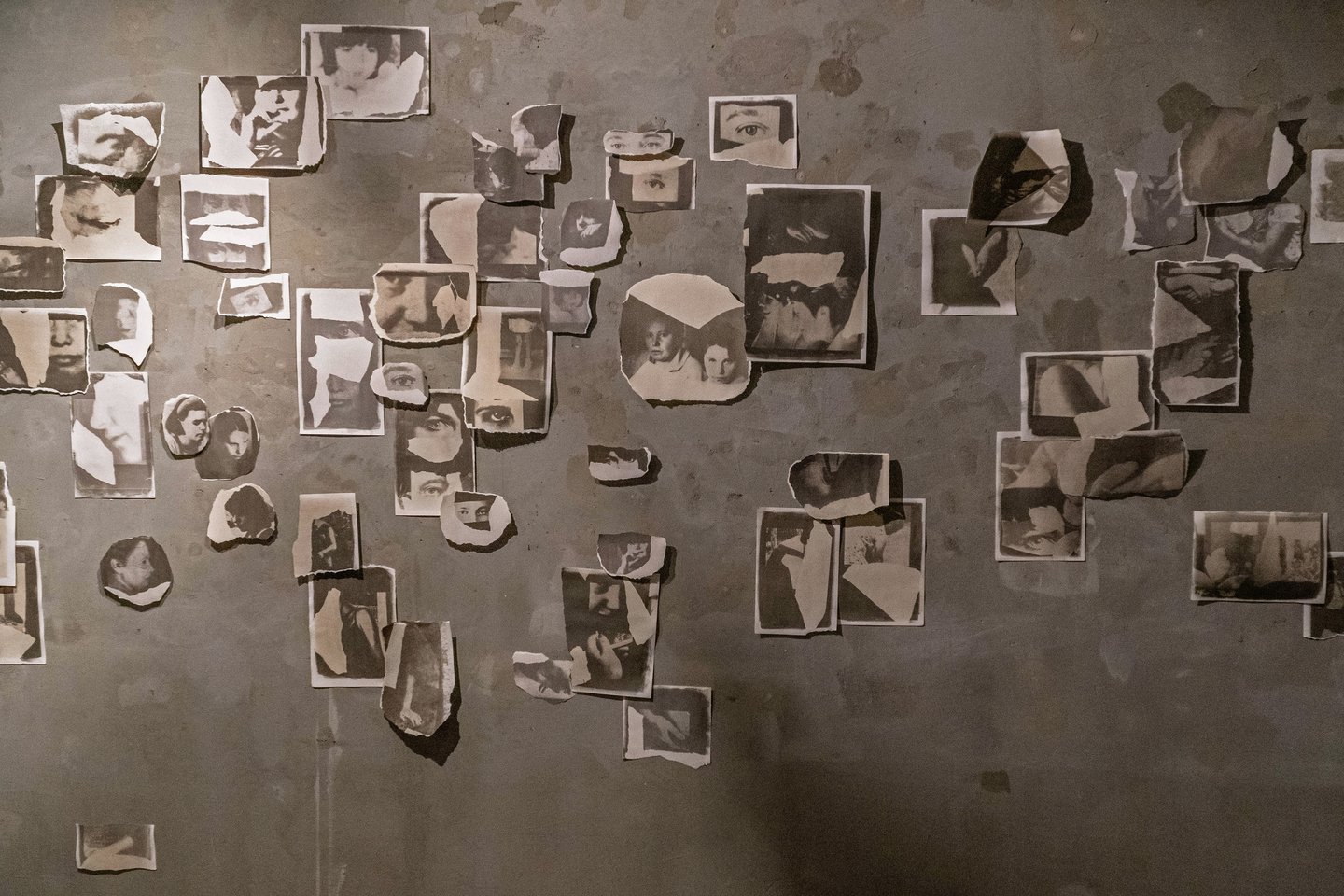

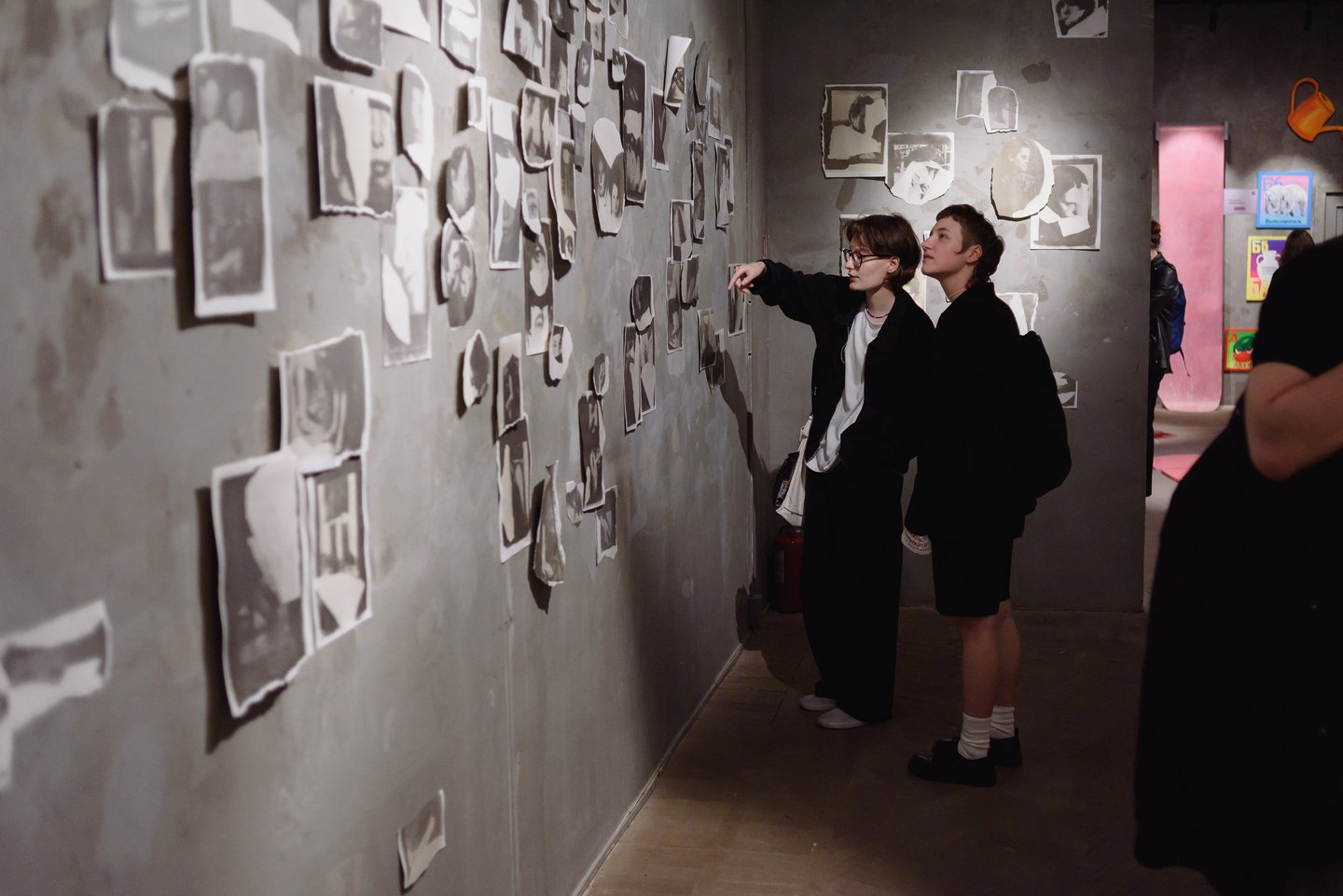

When I was six years old, I was adopted and my name changed. In family has a detailed history of my life up to adoption, but it’s not it’s connected to my memories. There are two girls in my life, with a different past and a real one. One name is Tanya, and mom is happy to remember what she was like when she was a baby. There are also photos on which are in the little girl’s family will recognize. Second — Sasha — gathers its memories, unsuccessfully trying to find in remember the support and prove your own reality. Her photo of — is the first image, on which I I recognize myself, though I in this is not quite sure — how many how I would not seek, I still remain a stranger to myself. Around these photos there’s an installation that’s going to grow, and it’s going to be on the 'nbsp; the two sides talking about the 'nbsp; the memories — from the 'nbsp; the one side representing the 'nbsp; the version of me that I’m remember, with the 'nbsp; the other — the one that I’m not I remember at all.

Attempting to gather a complete picture of the past is doomed — the memory body remains fragmented, mobile, composed of lacunas and voids.

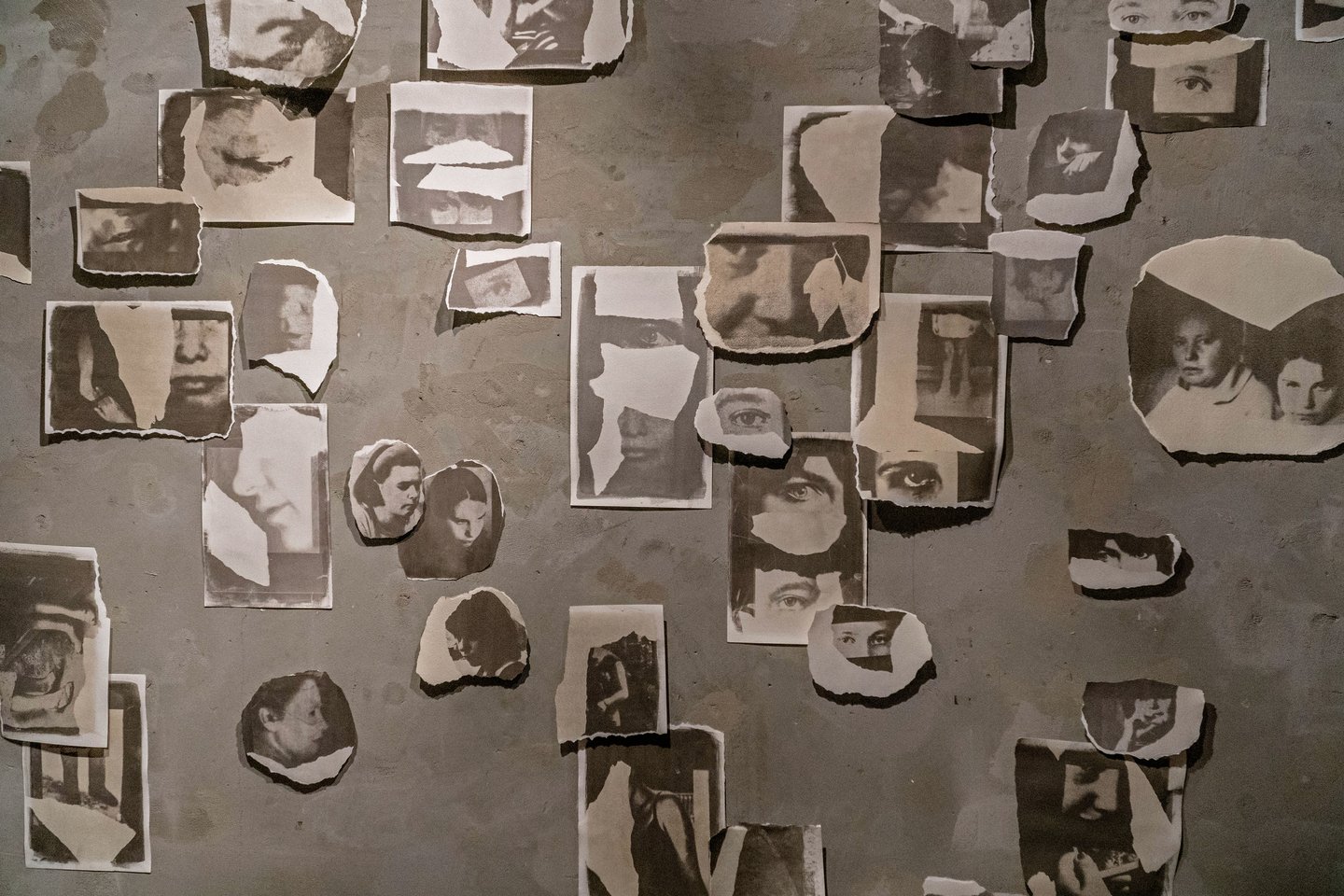

The family records don’t have my early childhood photos, and there’s no sign of me being under the age of six. The images gathered here are a game of random resemblance, an attempt to compare people who only have a name in common. I asked my socks and one-names to send their children’s photos, collecting some kind of archive. Like memory, this archive has no structure, we see only interlocking perspectives and unrelated people. We have a habit of looking for similarities and differences, guessing connections. Did you have the same sweater, like a hat, or maybe a picture from a daycare centre? The memories of different people can cross in any way, and now we’re almost ready to recognize ourselves in a random photograph.

I’ve always been interested in finding and finding similarities between me and other women in my family. Looking at the features of my face, the shape of my body, and taking gestures — as a foster child — all that makes up a common pattern of family stories are important to me. The search for similarities and differences has helped me to live in a sense that is inseparable from my experience, that is, a sense of isolation, that I cannot feel connected with my family. The similarities between us lead me into the history of a family with no biological relationship, but there is a common experience and memory.

Common memories bring us together, make us really alike, like all people, especially those who have lived with each other for many years.

Their active living somewhere between the actual and unrecognizable modified memory makes these images ghastly. As ghosts, memory sites disrupt the tightness of the present, both in the past and as if even in the future.

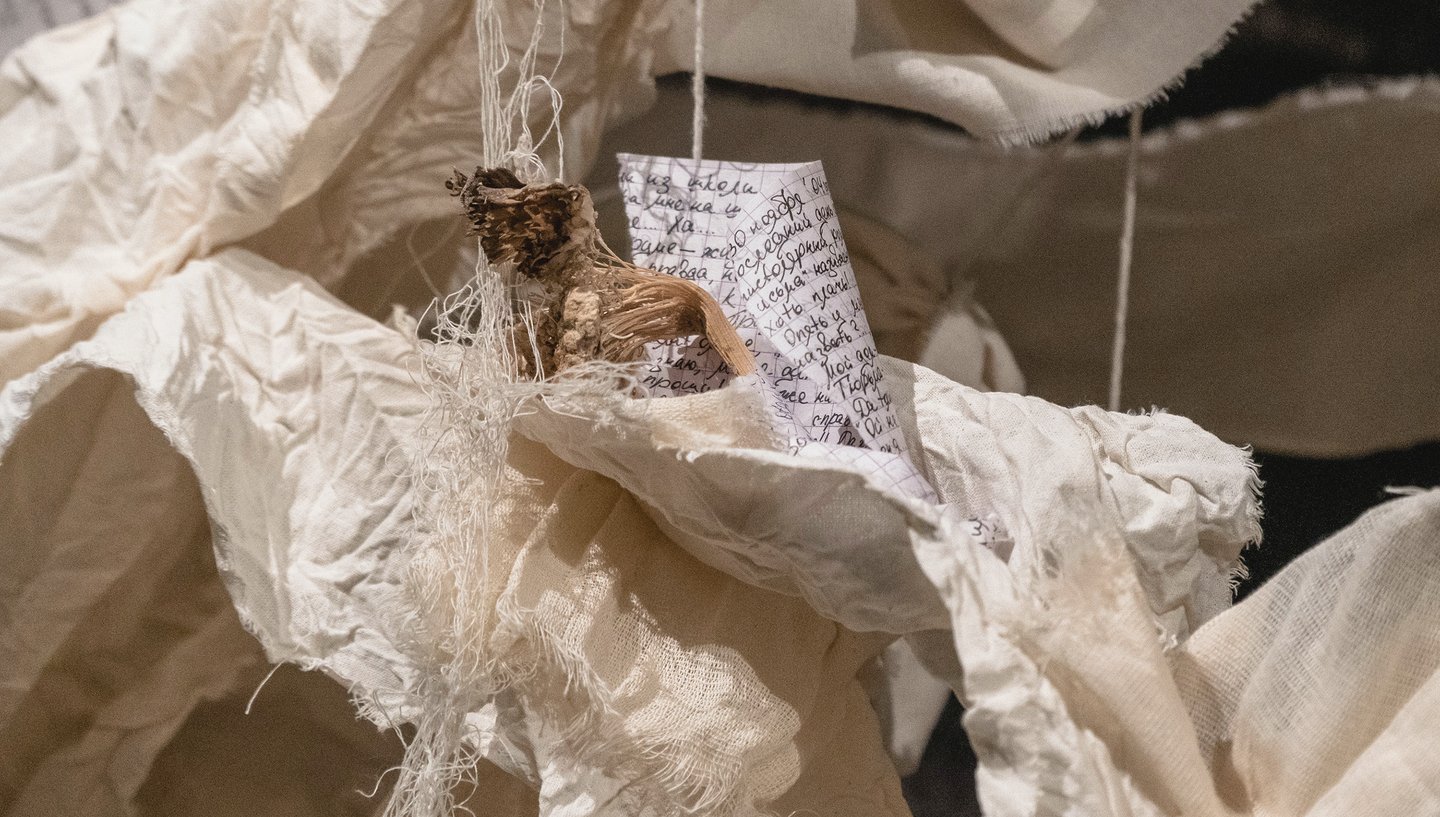

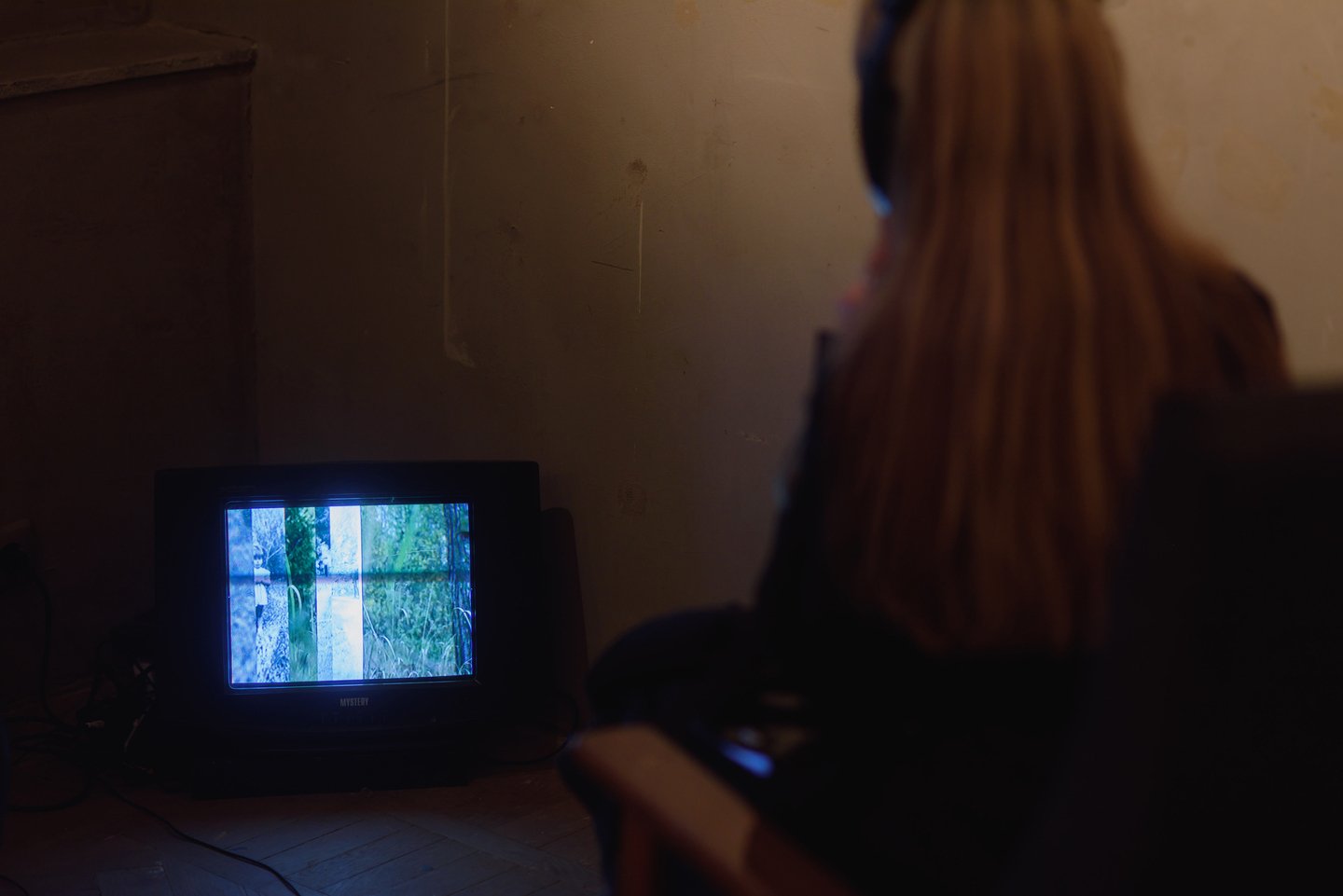

It’s based on a series of stories about two things that matter to me at home. There’s only one blank picture left of them, and the spin around them, trying to recreate images of forgotten spaces. The obsessive idea of remembering a place from the past from which there is little left is turning into many attempts to extract as much information as possible from one image. Out of the spinning of the preserved and thought-out pieces and the void between them, there’s a mechanic of memories.

Searching for sliding parts, trying to catch their vague silhouettes, all comes down to finding the contour of memory of this place, consisting of memories and voids between them.

Trying to transform memory has always been an important part of the relationship with the past in my family. In a suitcase with pictures, I often find small stripes of pictures or pictures where only space is preserved. The memory behaves as well, while keeping small details, washing whole pieces. That’s what happened to these pictures, where the whole family will recognize me, telling me that they remember exactly where and when it was taken. I found this place all grown up, but I couldn’t remember it, but I took a little bit of herb with me, as proof of the reality of my journey.

#h6>

I’ve been keeping my treasure collection since I was a kid, and she’s been traveling with me everywhere in a matchbox. For me, these objects are not so much a memory as an anchor to prove the reality of the past. The collection of such collections brought together many children in the Soviet and post-Council space. Along with mine, there are a number of collections here that have been left unattended. The earliest of about the 1950s, and it consists mostly of badges, the latest of mine, belongs to the nineties. And if I can remember what happened with the objects in my collection, then the rest of them can only be fantasized.

#h6> Trying to see the collection of human beings, we try these things on to ourselves, wondering: What did my treasures look like when I was a kid? What distinguished them from others? Who did I show my collection to?

Photos: Ruslan Hafizov * Alexandra Pavlovsky