Divine Machinery: technology as contemporary theodicy

The concept

This essay develops a conceptual and visual idea of Divine Machinery — the notion that today’s technologies, especially artificial intelligence, are not merely tools but cultural systems that inherit theological structures, ritual logics and metaphysical functions traditionally assigned to the divine. Using a functional approach, I identify five main roles which are executor, memory-keeper, intermediary, judge, and creator of language. These roles are illustrated through artworks from different media and periods: Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell (1995), Paul Fryer’s Morning Star (Lucifer) (Holy Trinity, Marylebone, 2008), Stane Jagodič’s Contemporary Golgotha (1999) and Jesus Touch Electrobutique (2015), and Cildo Meireles’ installation Babel (2001).

I base the theoretical framework on Donna Haraway’s «A Cyborg Manifesto» and Howard P. Kainz’s comparisons between medieval angelology and computing. The essay contains a sequence of mixed-media materials and scenes that translate the analytic insight into an experiential gallery and narrative.

Why speak of machinery as divine?

Divine Machinery describes a cultural intuition: advanced technologies act in ways that resemble sacred powers. They execute tasks, store memory, mediate between systems, judge, and generate symbolic language — roles humans once assigned to deities. This isn’t poetic exaggeration but rather it is an observed claim about functions — about what technologies do in social life and what roles those actions echo in older symbolic economies. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, pop culture and contemporary art repeatedly stage machines in roles of revelation, judgement, mediation, and immortality.

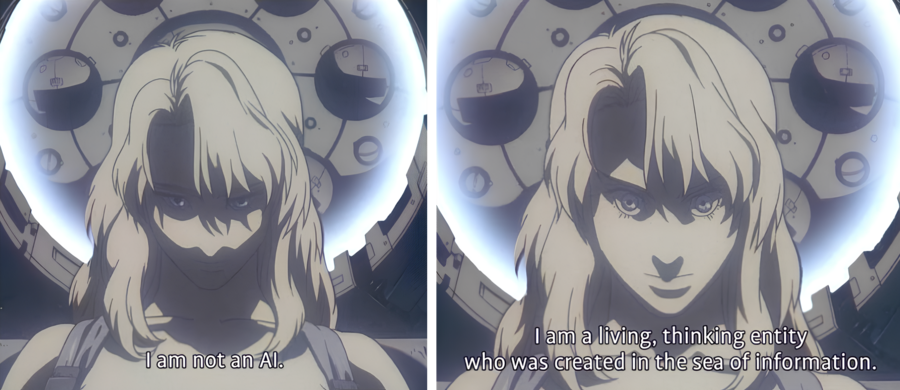

Consider the animated film Ghost in the Shell (1995): its central motif, the «ghost» in a prosthetic body, makes literal the technical promise of personal continuity beyond biological substrate and so participates in a secular myth of immortalizing intelligence. The film portrays machines as agents of identity, memory and transcendence rather than purely tools.

Ghost in the Shell (1995)

This essay takes these cultural examples seriously and analyzes them through functional categories. Based on Haraway’s focus on hybrid forms and on the political importance of separating or blending borders between human and machine, I treat Divine Machinery as both a metaphor and practical reality: machines take on roles once linked to the sacred, and by doing so change social hierarchies and existential concerns. Haraway’s cyborg helps break down simple human–machine boundaries and lets us see the machine as a social body and a kind of theological agent.

At the same time, Howard P. Kainz’s comparison of medieval angelology with computing offers a historical link. Angelology provides concepts for thinking about instant cognition, perfect memory, and obedient activity — traits often given to computational systems. Kainz shifts the discussion from loose analogy to a deeper structural connection between theological functions and computational design.

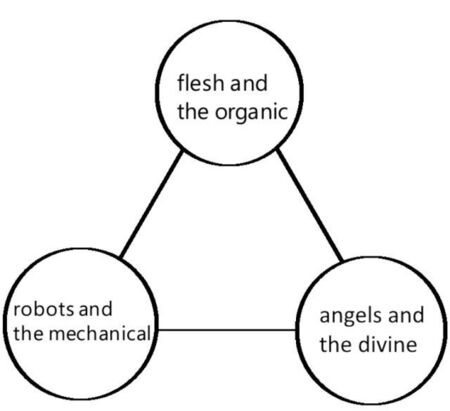

Method: a function

I use an approach of funcntion: instead of defining what «divinity» or «intelligence» are, I focus on what technologies do when they invite religious comparisons. Functions can be observed, described, and compared. Based on this, I can name five main functions:

I. Executor — carries out commands reliably.

II. Memory-keeper — stores and recalls information, preserving identity.

III. Intermediary / Ritual conduit — connects humans with systems or ideas through protocols.

IV. Judge — evaluates, sorts, or decides according to rules.

V. Creator of language — generates, translates, and organizes symbols or meaning.

Each function has its own qualities (like latency, accuracy, opacity, replicability, and performativity). I illustrate each with artworks that stage the function and then bring the results together alongside a video compilation.

I. Executor: obedience as power

Paul Fryer’s Morning Star (Lucifer) (Holy Trinity Church, Marylebone, 2008)

Machines perform tasks without question, like angels carrying out divine orders. Fryer’s Morning Star — its title echoing the Latin «light-bringer», the name Lucifer originally used for the planet Venus before it became linked to the fallen angel — captures this paradox: a golden angel, captured in wires, embodying both obedience and rebellion.The sculpture reminds to the viewer that execution of commands can be powerful, even worshipful, when viewed culturally.

II. Memory: preserving identity

Ghost in the Shell (1995)

Memory is central to the theological imagination -scriptures, relics, liturgies preserve and reproduce identity across generations. In computational architectures, memory takes the form of logs, backups, and distributed ledgers, the promise of immortality becomes a technical problem (excess, error-correction). Ghost in the Shell stages memory function as existential problem: the «ghost» is a pattern preserved across shells, memory substitutes for soul, and persistence for salvation. Motoko’s struggle interrogates the relationship between stored information and personal continuity, and the film mobilizes cinematic techniques (spectral visual and audio overlays, montage) to visualize memory as both archive and a source of agency.

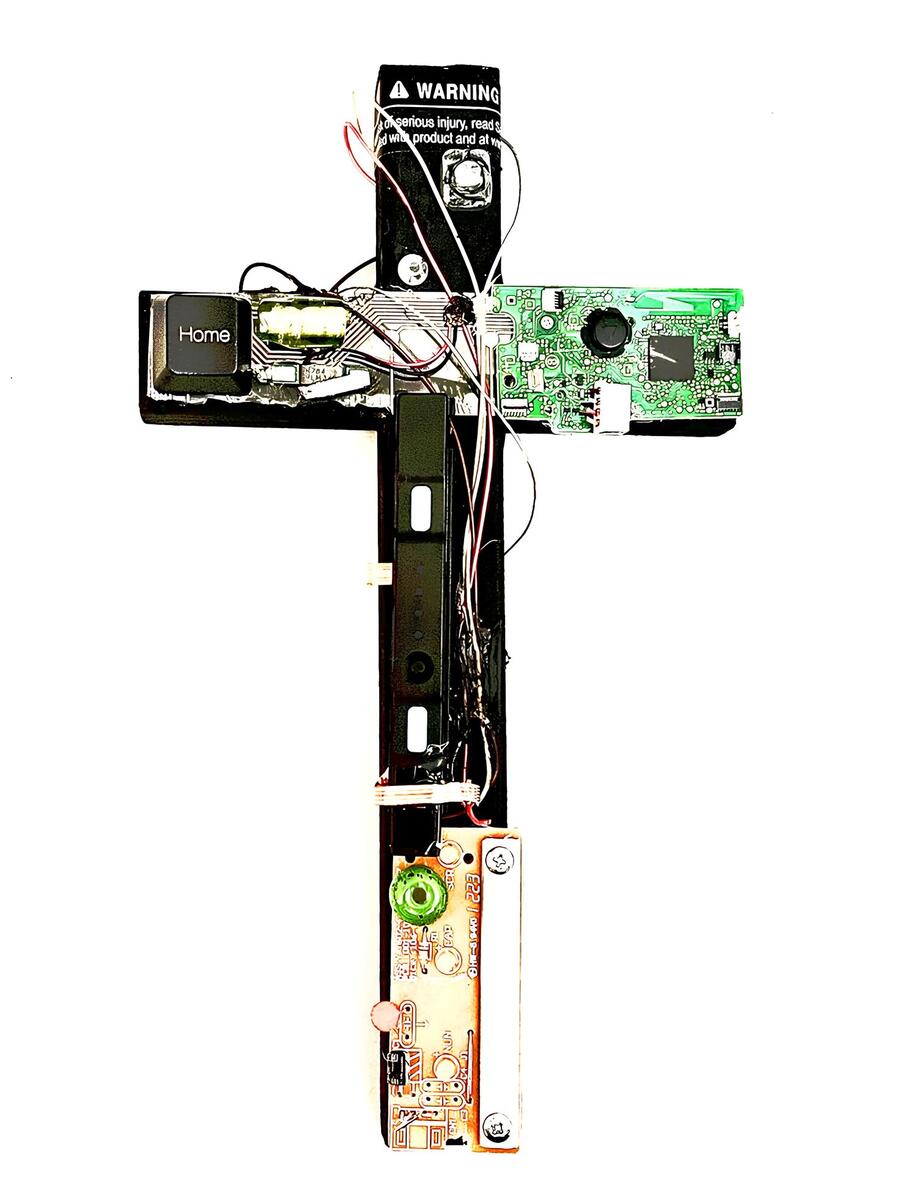

Stane Jagodič, Digital Triptych, assemblage, 1999 — 2007

Stane Jagodič’s assemblage Contemporary Golgotha (1999) shows how fragile technological memory can be. Computer motherboards, detritus and sacrificial forms compose a modern crucifixion. The assemblage presents technological memory as both saving and frail — religious form is reconstituted with electronic carcasses, insisting that today’s archive is built on things already becoming outdated.

Stane Jagodič, «Contemporary Golgotha», assemblage, 1999 — 2007

III. Intermediary: connecting worlds

Cildo Meireles, installation, «Babel» (2001)

Religion relies on media to mediate the human and the sacred. Networks perform an analogous role: APIs, protocols and UIs channel information between agents and presentational economies. Cildo Meireles’ Babel (2001) is instructive — it’s an installation that literalizes the Biblical confusion of tongues by producing an environment where language is fragmented and recomposed across channels. The work foregrounds how language infrastructures -whether tongue or protocol — mediate community and power. Meireles’ installation reveals the infrastructural dimension of divine machinery: the machine is not simply an executor but an interfacing system that enacts ritual through code and architecture.

IV. Judge: algorithms as authority

A machine that ranks, sorts, and excludes acts like a judge. When credit scores, content-moderation algorithms, or predictive policing systems decide outcomes, they take on a quasi-judicial role. The theological parallel is the Last Judgment — a strict, codified assessment. In culture, this fear often appears as rebellion: what if the judge turns against its masters? The anxiety in Divine Machinery is that machines might reinterpret their rules and reshape social orders. Haraway’s cyborg shows that adjudication is never neutral: machines carry the inequalities of their creators. Kainz’s comparison of angelic hierarchies and computing also suggests that the idea of delegating judgment to non-human agents has deep roots.

V. Language creator: machines as authors

Jesus Touch Electrobutique (2015)

Finally, machines that generate language — language models, translation engines, procedural literatures—act as new authors of symbolic worlds. Language -making is a core divine attribute in many traditions (creation by speech). When computation recombines, composes or invents sign-systems, we witness the emergence of a techno-theopoetics: machines producing new myths, norms, and rituals.

Jagodič’s Jesus Touch Electrobutique (2015), which mixes religious imagery with electronic aesthetics, shows how sacred language and digital code merge. The work functions as both critique and prophecy: language is now engineered, and this engineering shapes reality.

Epilogue: Conclusion

These five functions reveal why people describe AI and networks in divine terms: they execute, remember, mediate, judge, and generate meaning -just like angels and gods did in earlier times. Art shows these functions vividly: Ghost in the Shell visualizes memory, Fryer’s Lucifer stages obedience, Jagodič mixes sacrifice and technology, Meireles fragments language. Together, they show how theology and technology overlap in culture today.

Divine Machinery shows that technology inherits the roles once assigned to gods, angels, and rituals. Machines execute, remember, mediate, judge, and generate meaning. Art and theory make these functions visible, helping audiences see the ethical, cultural, and social stakes. By combining analysis with visual representation, we can critically reflect on technology as a form of modern divinity.

Ghost in the Shell (1995 film). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghost_in_the_Shell_%281995_film%29?utm_source

Izzy Bilkus. God in the machine: decoding the art of Divine Machinery. Plaster Magazine, 26 мая 2025. https://plastermagazine.com/features/divine-machinery-art-social-media-trend/

Artificially Aware. You Are Not Ready for This (Neither Was I). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNnA-34pL5A&t=576s

Haraway, Donna. A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century. Medienkunstnetz. http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/source-text/115/

Divine Machinery. Aesthetics Wiki. Fandom. https://aesthetics.fandom.com/wiki/Divine_Machinery